The value of bad ideas

If we never talk about any ideas that most other people dismiss as bad, some truly great ideas will invariably be lost. Many of the most important ideas throughout history were publicly ridiculed in their time:

- The earth is round.

- The earth revolves around the sun.

- Human beings evolved from apes.

And so on.

Being a contrarian can be risky and lead to ostracization in some areas (religion and science, for example), especially when it's difficult to prove that you are right. However, being a contrarian in cases where the market quickly and decisively signals that you are right can be extremely rewarding. We see this in both the financial world and and the startup world.

Warren Buffett famously built one of the greatest investment records of all time partly through following the contrarian principle: "Be fearful when others are greedy and be greedy when others are fearful."

Of the top five most valuable companies today, four started off as seemingly terrible ideas:

- Steve Wozniak went to HP five times with his designs for the Apple I, but they turned down his proposal to build it.

- Microsoft's first product was a BASIC interpreter for approximately 2,000 Altair computer hobbyists.

- Google was the latest in a stream of search engines, nearly all of which were losing money because people leave the service after it gives them what they want - and a good search engine just makes them leave faster.

- Facebook was the latest in a stream of social networks, focused on helping a very small group of people with no money (college students) to waste time on the Internet.

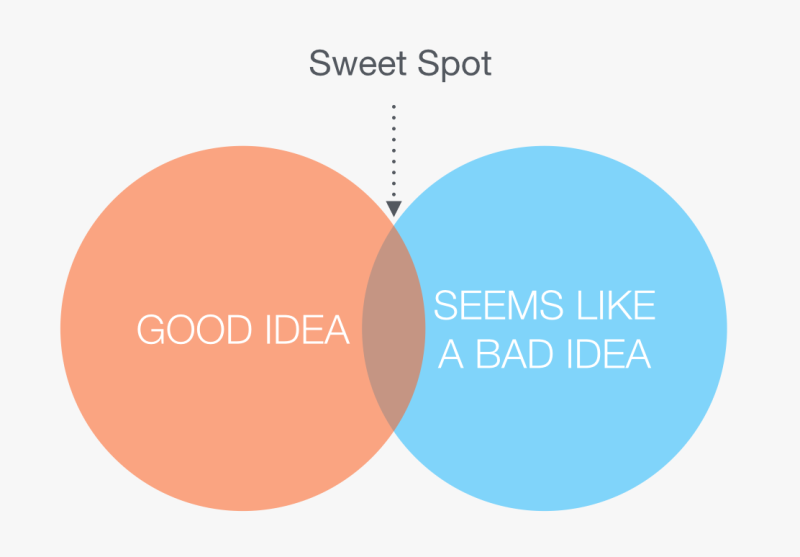

The diagram in the cover photo is attributed to Peter Thiel during a talk at Y Combinator, where he emphasized the importance of that intersection between seemingly bad ideas and good ideas. It's a "sweet spot" because this overlapping area faces much less competition in the market (since everyone else would have dismissed such ideas).

That said, the diagram also clearly shows that the majority of seemingly bad ideas are in fact bad. So then the question becomes: how might we determine whether a seemingly bad idea is actually good?

The short answer is we can't. If we had a simple formula or strategy for figuring it out, we could probably run the most successful venture capital firm of all time. However, at least in the context of business-related ideas, there appear to be some heuristics we could use to assess whether we are on the right track with a specific idea.

A sturdy intellectual framework supports it

In most cases, reality eventually overpowers prevailing beliefs. Advances in science are the best examples of this. The effects of relativity can be measured, clearly demonstrating inaccuracies in Newton's laws. Warren Buffett's early utilization of the margin of safety to buy stocks of companies trading below the value of their cash on hand is another example.

The market is small now, but can be huge later

Both Apple and Microsoft blossomed because the initially contrarian hypothesis that personal computers will become ubiquitous proved to be correct.

A similarly contrarian hypothesis today is that cryptocurrencies will become ubiquitous in the future. Only time will tell in this case.

People really love what you made

Both Google and Facebook made something that users absolutely loved. They got all the users first. Getting all the users turned out to be much more difficult than monetizing them.

Not everyone needs to love it at first, but there needs to be some group of people who would be extremely sad if what you make goes away. Airbnb is perhaps the most recent benchmark for this. Renting airbeds in someone else's apartment seemed crazy at first, but enough people loved the idea for it to eventually get off the ground.